1941.

Roger Boutet de Monvel (1879 - 1953), the eldest son of the painter and illustrator Maurice Boutet de Monvel (1850 - 1913), who was a writer, completed the writing of his memoirs.On reading his brother's manuscript, Bernard Boutet de Monvel (1881 - 1949) notices that the latter only refers to their father very superficially, lingering over descriptions he considered to be a lot more trivial, such as that of Prince Constantin Radziwill in his mansion in Ermenonville, where Roger Boutet de Monvel stayed for a while.

Bernard Boutet de Monvel therefore decided to fill this void by including his own memories of his father in the paper, of which I have retranscribed some large extracts connected to the man and his work below.

This text by Bernard Boutet de Monvel, like Roger Boutet de Monvel's manuscript, has remained unpublished until today.

Maurice Boutet de Monvel was charm itself, with this elegance which either you've got or you haven't, whether you're in a dressing gown, formal dress or a bathing costume. He was a little larger than average but was so perfectly proportioned that he appeared tall to anyone. He carried himself charmingly, with a very fine leg, ravishing high insteps and, always adopted graceful poses quite naturally.

Maurice Boutet de Monvel was charm itself, with this elegance which either you've got or you haven't, whether you're in a dressing gown, formal dress or a bathing costume. He was a little larger than average but was so perfectly proportioned that he appeared tall to anyone. He carried himself charmingly, with a very fine leg, ravishing high insteps and, always adopted graceful poses quite naturally.

His face, both gentle and vigorous, featured good bone structure. His brown eyes were sparkling and tender, his nose uneven, aquiline and fleshy at the end, and he had an African complexion.

His wavy and very black hair had greyed early. Like the artists of that age, he wore a short pointed beard and masterful moustaches.

For a long time he dressed himself in his own unique style, dwelling on the fashions of his youth, with very narrow-fitting trousers sporting small checks, which suited his slim legs and his narrow hips, and were accompanied by flat-brimmed top hats.

To my great regret he later gave this up and for the last twenty years of his life, he adopted grey swansdown suits with trousers which were the fashion for painters of the day, which had broad tops and were narrow at the ankle. These eternal suits which, I recall, cost fifty Francs, came from an old shop on Ile St-Louis, which has since disappeared, where you often dressed yourselves, and which was called "Le petit matelot".

With these clothes he cut no less elegant a figure and looked miraculously young. This is so true because at the time of the memories I refer to, he would barely have been forty years of age, old enough to be the son of the old man that I am today, alas.

I can still picture him now through the window of Rue Condé, where we lived, merrily wending his way to his studio, followed by his gun dog, Fly, climbing up Rue Crébillon, without an overcoat summer and winter alike, and so alert twirling his cane. How he loved life and youth!

If I've spoken about his appearance first of all, it's because I know how much he set store by the so-called vanities of outward appearance and how much he dreaded the effects of age and physical degeneration, as if he pre-empted the terrible blow that fate had in store for him whilst still in his prime, on the eve of his fiftieth birthday, as luck was finally smiling on him...

He had the most charming spirit and heart; chivalrous and generously enthusiastic for anything noble. He had all the true virtues, the simplicity and grace of a man of noble birth. He was full of spirit and great sociability. His conversation was charming and he enjoyed it. He had a great sense of irony and was a real tease, though never with even a hint of spitefulness...

He loved children and would have valiantly raised eight or ten as his parents did, if the heavens had given him them. How gentle he was with us: he told us endless stories of his own fabrication, which we never tired of listening to, open-mouthed; stories which kept going back to an old woman and a famous little red horse, both of which played the heroes.

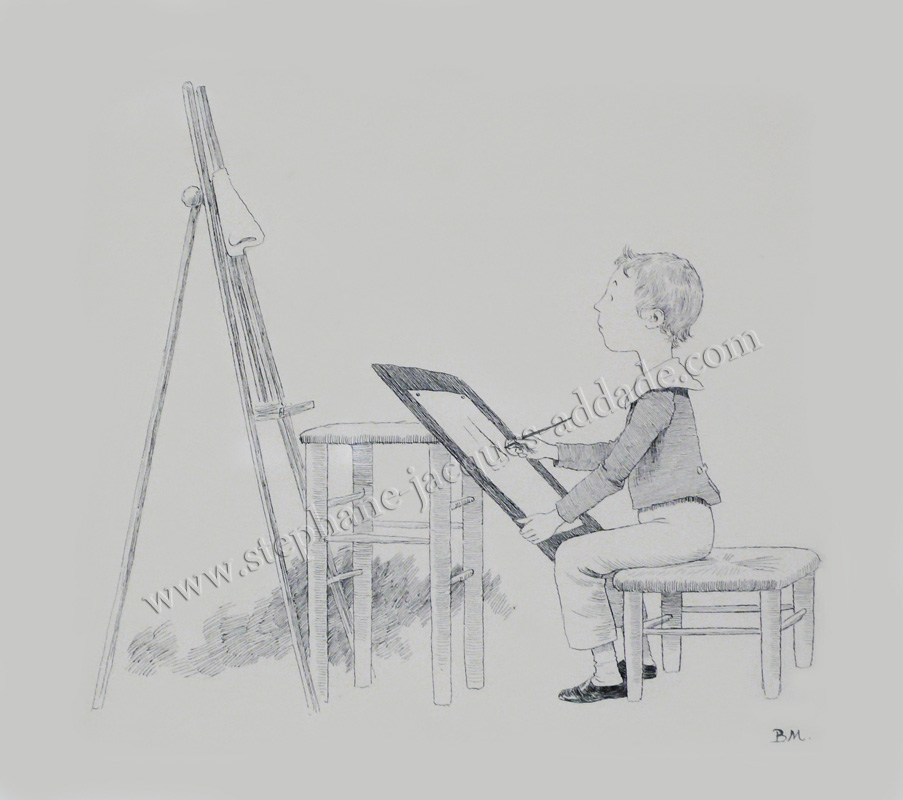

A big treat as young children, was to be taken along to his studio in Rue Rousselet(1). At the time I was four or five years old; I can still clearly see this studio, which I have a photograph of and which appeared immense to me. It looked out onto the vast garden of a religious establishment. Maurice Boutet de Monvel always settled me in front of the large manuals like a good boy. They showed the labours of Hercules dealt with like Etruscan vases in the red-figure style on a black background and they just blew my mind. I still remember the hero's battle with the Lernean Hydra and its innumerable and terrifying heads.

A big treat as young children, was to be taken along to his studio in Rue Rousselet(1). At the time I was four or five years old; I can still clearly see this studio, which I have a photograph of and which appeared immense to me. It looked out onto the vast garden of a religious establishment. Maurice Boutet de Monvel always settled me in front of the large manuals like a good boy. They showed the labours of Hercules dealt with like Etruscan vases in the red-figure style on a black background and they just blew my mind. I still remember the hero's battle with the Lernean Hydra and its innumerable and terrifying heads.

Very often since that time, I've sadly retraced my steps in front of this quiet Rue Rousselet when I lived in nearby Rue Monsieur (2), and looked up to the top of this house where my father worked from such a young age, so full of hope in his life with so many noble ambitions. I thought about the windows (3) in his studio, which have disappeared now that the house has been hideously modernised and raised one floor higher.

Then came his definitive set-up at 6, rue du Val de Grâce (4) , in the fabulous studio he spent the rest of his life as an artist, which has so many ties with the beginning of my own. It was really enchanting this studio and took up the whole of the first floor of a kind of pavilion, lost in the gardens. In my youth, "L'atelier de papa" (Dad's studio) seemed to be the height of splendour with its large tapestries, its box beds, its couches and its large sideboards...

At the far end, there was a kind of little aerial conservatory which Maurice Boutet de Monvel had built and where he worked virtually the whole time. At the other end a long staircase led to a vast dimly-lit cupboard, where piles of olds canvasses were stacked and a thousand different objects were discarded and buried beneath ancient layers of dust. I relished rummaging around there.

On a particular day, Maurice Boutet de Monvel did just that, under my dismayed gaze, resulting in absolute carnage of former studies, which had ceased to appeal to him and among which, I very much fear, were the last of the old paintings of his early Algerian work that I love so much.

I returned, heartbroken, into this house when I went to pose for Paul Manship (5) , who was set up in a neighbouring pavilion. The studio is still the same but the gardens have disappeared and all the old charm has gone...

Each morning, Maurice Boutet de Monvel headed off for the studio, chased out of his bed by my impetuous mother who found lie-ins to be abhorrent. He immersed himself in a full bath of cold water; a barbaric custom which was quite popular at that time. It was thanks to this practice that he could go out without an overcoat in the depths of winter with the look of a twenty-year old boy. He hastily returned for lunch and went back again until night fell, before going fencing at the Kirshoffer hall. His existence revolved around absolute regularity...

Nothing can really give a precise idea of who the man was, but the artist is still here, before our gaze, as alive as the day when he created his works.

A great artist is a person who creates a work of art which nobody had done before him or her and that nobody would ever be able to recreate in similar fashion. This is very much the case for Maurice Boutet de Monvel.

His first paintings in his youth already testified to his exceptional talents... As such it was decided that the young Maurice Boutet de Monvel would enter Julian's studio(6), where everyone went at that time, due to a lack of Fine Art schools. He joined the mediocre Jules Lefèvre (7) and the annoying Cabanel(8) . "Les Julians (9)» formed a kind of freemasonry, who stuck together for the Shows – which were so important at that time – the awards, the official commissions and the decorations. Maurice Boutet de Monvel, approach to be recruited, refused the offer and went instead to Carolus-Duran's studio (10).

He would never be part of any clique or set. His talent was unlike that of any of his masters or friends and he always lived and worked alone. I cannot blame him, having followed his example and not regretting it, though I'm well aware of the indisputable harm that can come of it, if not to the artist's talent, then at least to his interests. But what peace can come of working totally independently. It's the contemplation of the retreat compared with the rule of the cloister.

Maurice Boutet de Monvel began by exhibiting large highly academic paintings, which enjoyed very academic success but were, admittedly, terribly dull: a Bon Samaritain (11) (Good Samaritan), a Marguerite à l'église (12) (Margaret at church), La leçon avant le Sabbat (13)(The lesson before the Sabbath). None of this gave any indication of the dazzling personality which was to suddenly burst forth. And yet some very remarkable sketches and drawings for these paintings date back to this time... A certain Poursuite de la Fortune (The Pursuit of Fortune) is one of the most outstanding romantic works there is. There are military scenes which depict death, and some tragic judicial figures... However, it then seems that Maurice Boutet de Monvel was betrayed by the craft of painting, colour and materials, as soon as he transfers his compositions to canvas: indeed they immediately lose their fieriness and their freedom. In Aulnoy(13) I have La leçon avant le sabbat (15) and two or three large paintings from this time. Some day I shall have to resign myself to reverently destroying them to preserve the memory of my father, which it would only harm. And yet, from this same time came a fabulous half-finished painting of Suzanne au bain (Suzanne in the bath).

Everything about it is remarkable: the composition, the design, the merits, the colour even: a really fine painting. Doubtless it was around this time that he went on his first trip to Algeria and Tunisia (16) from which he brought back some exuberant, dazzling studies. I'm familiar with about ten such paintings. A second trip(17) saw him bring back more very fine works but already they were less free. Those from the third voyage(18) are drier, still full of qualities and carried out with extreme conscientiousness but unquestionably less brilliant.

However, as remarkable as these studies and certain oriental figures were, along with the landscapes of Touraine and later Nemours, they don't portray a character with as remarkable a personality as his painted compositions.

Nemours, they don't portray a character with as remarkable a personality as his painted compositions.

Nemours, they don't portray a character with as remarkable a personality as his painted compositions.

Around this time, whilst he was influenced by the Spanish, Maurice Boutet de Monvel painted a few men's portraits in a dark style. Again this wasn't his true calling. From this time though came two beautiful faces belonging to Miss Mainguet and Miss Bourdel.

Maurice Boutet de Monvel married without a penny to his name to Jeanne Lebaigue, who was equally impecunious. As such they spent the early part of their marriage living with my maternal grandparents.

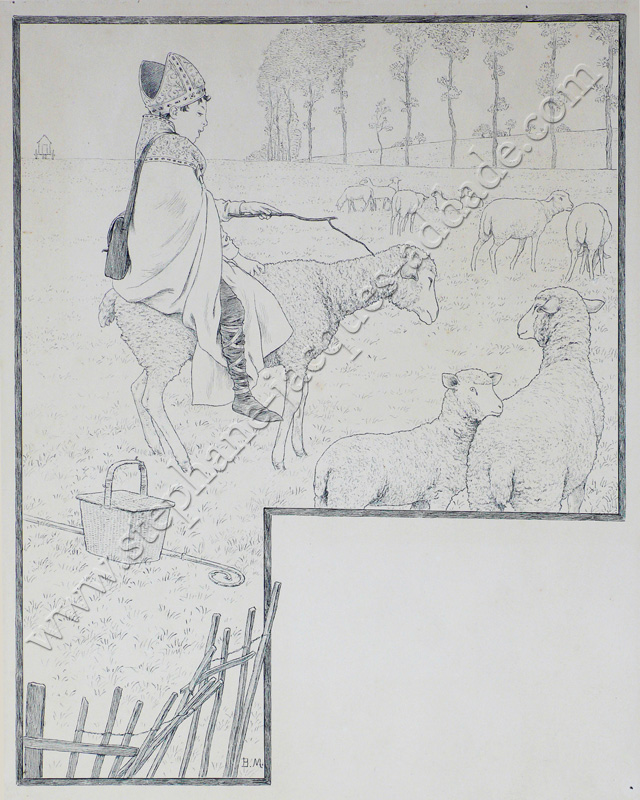

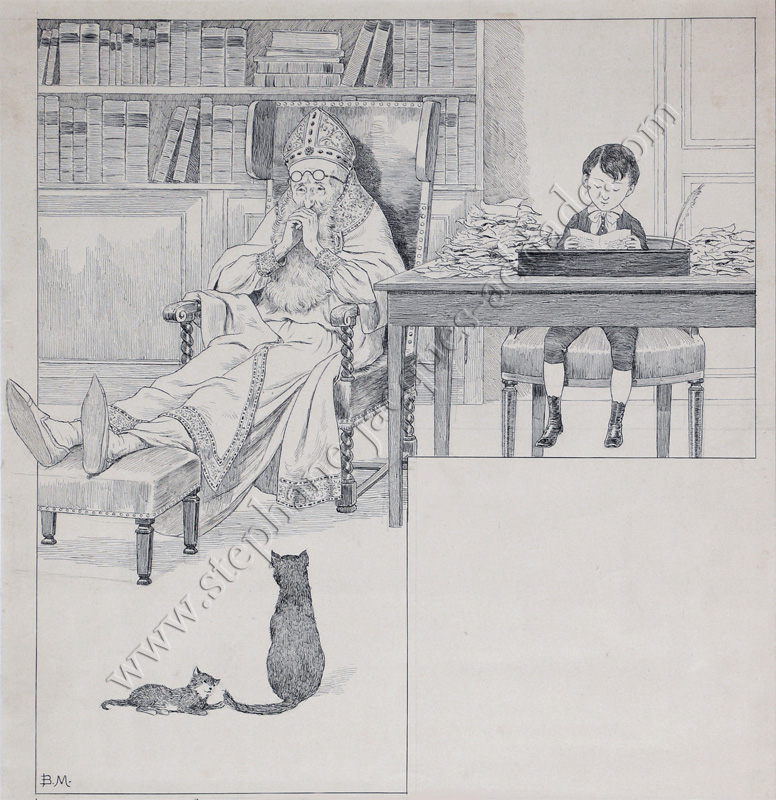

I don't really know how my father then obtained a commission for an illustration of a potted Histoire de France (19) (History of France)... worth ten Francs a painting. It was a real godsend! This at least seems to have guided part of his career. The paintings appealed to the publisher Delagrave(20) , who then requested him to do regular illustrations for a children's book, Saint Nicolas (21) . Maurice Boutet de Monvel worked on this for around ten years: small paintings for ten Francs, the big pages for fifty.

Maurice Boutet de Monvel was immortalised in the small unmatched and unrivalled illustrations: he'd straightaway found a formula of his own when there was no hint of such a thing prior to that. I have really never come across such a thing with anyone else. Moreover, the freshness of sentiment, the spirit and the perfection in the execution force admiration...

NOTES :

(1) Maurice Boutet de Monvel's studio was located at 17, rue Rousselet, Paris. He settled there in 1876, having successively occupied a studio situated at 1, rue des Deux-Portes (a current section of the Rue des Archives), then another situated at 81, boulevard du Mont-Parnasse in Paris.(↑)

(2) Bernard Boutet de Monvel lived at 7, rue Monsieur, in Paris, from 1921 to 1926. (↑)

(3) An old-fashioned term for windows.(↑)

(4) Maurice Boutet de Monvel set himself up in this studio in 1893. (↑)

(5) The sculptor Paul H. Manship (1885 - 1966), who in 1927 (?) made a medallion in low relief of Bernard Boutet de Monvel's profile.(↑)

(6) In Paris in 1867, Rodolphe Julian (1839 - 1907) founded a much renowned painting and sculpture academy which, for a lot of young painters of this generation, was an alternative to the college of Fine Arts. (↑)

(7) Jules Lefèbvre (1836 - 1911) was an academic painter and teacher at the college of Fine Arts and the Julian Academy. Maurice Boutet de Monvel and he always retained close ties. (↑)

(8) Alexandre Cabanel (1823 - 1889) was a renowned academic painter and professor at the college of Fine Arts. The Fabre Museum in Montpellier devoted a sizeable retrospective to him from July to December 2010. (↑)

(9) The professors from the Julian Academy, who were all celebrated academic painters, enjoyed a certain influence at the Show. (↑)

(10) Charles Emile Auguste Durand also known as Carolus-Duran (1837 - 1917), a painter considered today to be academic but in his day he was hailed as modern due to his use of colour. He opened a painting studio for men in the autumn of 1872. He went on to open a second for women in 1874. The Palais des Beaux-Arts in Lille and Les Augustins museum in Toulouse devoted a retrospective of his work back in 2003. (↑)

(11) 1878 Show No.1625. Maurice Boutet de Monvel received a third place medal for this painting. (↑)

(12) 1874 Show No.1839 (↑)

(13) Show of French Artists in 1880 No.2700. Maurice Boutet de Monvel was awarded a silver medal for this painting. (↑)

(14) The Aulnoy Mill was the country house owned by Bernard Boutet de Monvel near Nemours. (↑)

(15) Today this work is kept by the Musée-Chateau in Nemours. (↑)

(16) As confirmed in a letter from Maurice Boutet de Monvel to Will Low, and as his passport confirms, the first trip to Algeria and Tunisia made by Maurice Boutet de Monvel dates back to the spring of 1876, contrary to the later date commonly suggested. (↑)

(17) The second trip took place in 1878. (↑)

(18) The third trip took place in 1880. This was the last, except for a quick journey to Algiers, in January 1893, for the death of his brother Etienne. (↑)

(19) Eudoxie Dupuis La France en Zigzag 1880 for which Maurice Boutet de Monvel created forty vignettes.(↑)

(20) Charles Delagrave (1842 - 1934) (↑)

(21) Keen to develop an editorial policy for his bookshop for the attention of children, Charles Delagrave founded Saint Nicolas: An illustrated magazine for boys and girls in 1880, modelling it on the magazine of the same name founded two years earlier in New York by Mary Mapes Dodge. (↑)

Dernière modification par Stéphane-Jacques Addade, le 23/03/2015